Medical Innovation: Kidney Donation and Stem Cells

How a Clinical Trial Helped a Chicagoan Reclaim Her Health

Updated June 2024

After a kidney transplant and years on dialysis following an autoimmune disorder that attacked her kidneys, Margaret Rainey, of Hyde Park in Chicago, was separated from her passion — being part of the Muntu Dance Theatre.

Margaret knew that the immunosuppressant medications she needed to prevent organ rejection can also cause kidney damage and significantly shorten the lifespan of her transplanted kidney. So, she stopped dancing and instead focused on researching options to improve her health.

We are continuing to pioneer ways to get people off antirejection medications.— Joseph R. Leventhal, MD

Now, she is one in a group of kidney transplant recipients who does not need immunosuppressant medications thanks to a Northwestern Medicine clinical trial led by Joseph R. Leventhal, MD.

following her kidney transplant, Chicago resident

Margaret Rainey is now living medication-free thanks to

a groundbreaking clinical trial at Northwestern Medicine.

The trial involved using stem cells from donors to reprogram participants' immune systems to recognize the new kidney as their own. This allows patients to wean off of antirejection medications after a one-time stem cell transplant. Trials have been limited to living donor kidney transplantations at Northwestern Medicine, but Dr. Leventhal hopes to apply the donor stem cell approach to other organs, transplants from deceased donors, and patients who have already received a transplant and wish to stop taking antirejection medications.

"We are continuing research to develop cellular therapies that hold the promise of reducing the need for or eliminating the need for drug-based immunosuppression, which greatly limits the quality of life and how long patients live with organ transplants," says Dr. Leventhal. "The medications are very good at preventing rejection early on, but they have long-term side effects that really limit the benefit of the organ transplant for patients. We are continuing to pursue and pioneer new ways to try and get people off of antirejection medications."

Working Against Disparities

Margaret's experience is not only a personal triumph but also a step towards addressing health disparities. Black adults are disproportionately affected by kidney disease, yet they make up just 5% of clinical trial participants in the United States. With this in mind, Margaret knew this was bigger than just her own health.

"For many years, I would see stories about African Americans and kidney disease, and I would break out in a cold sweat," she says. "For a long time, I was afraid to look these things up, but once you're on dialysis and you're sitting on a machine every night, you start to research." Margaret says she was able to do her dialysis at home, but the daily treatment schedule significantly limited her freedom.

Margaret's journey led her back to what she was familiar with: her family.

Staying Close to Home

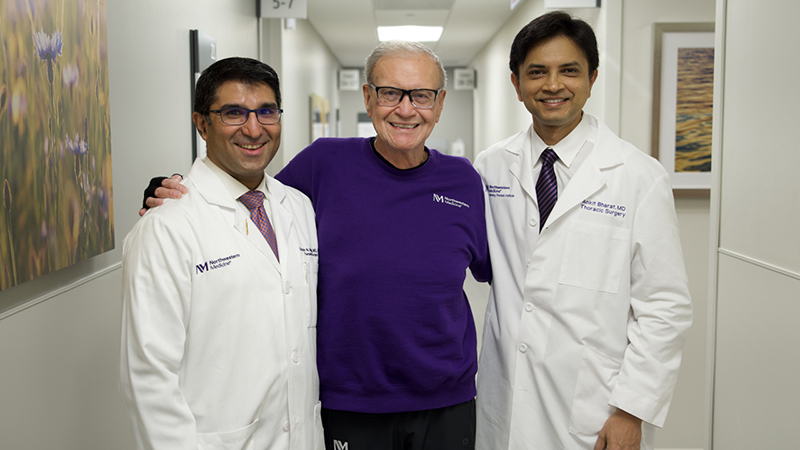

Margaret's daughter, elementary school teacher Arianna Barrett, was her kidney donor. Arianna lost more than 50 pounds to get healthy enough to donate a kidney and stem cells to her mom as part of the clinical trial. Margaret received the stem cells via an infusion the day after her kidney transplant. Northwestern Medicine Transplant Surgeon Dinee C. Simpson, MD, conducted the transplant.

Through the manipulation of Arianna's stem cells, Margaret's body now recognizes Arianna's kidney as its own. This means she does not need strong immunosuppressant medications.

"They are not only looking at the stem cells — they're looking at the kidney, too," Margaret explains of the care team's approach. "Even after I went home, I was coming to the hospital so often. It felt so good to be looked at."

"Ms. Rainey has been off immunosuppression medications since 2021," says Dr. Leventhal. "She's a great example of how we can hit a home run with this type of an approach."

Margaret is currently monitored by her hematologist every three months and her nephrologist every six months at Northwestern Medicine.

Now, not only has Margaret regained her health, but she is also back doing what she loves — traditional African dance.