Ultrasound Device Opens Blood-Brain Barrier

Clinical Trial for Glioblastoma Treatment Begins

Published July 2021

Glioblastoma is a complex type of cancer that forms in the tissue of the brain or spinal cord. And although relatively rare, it is the most common and most aggressive primary brain cancer in adults. Glioblastoma is also difficult to treat, as these types of tumors are resistant to many therapies.

Tumor heterogeneity refers to molecular variations between tumor cells. With glioblastoma, tumors are more likely to be variable, explains Northwestern Medicine Neurosurgeon Adam M. Sonabend, MD. This means every individual's tumor is different, so one standard treatment approach can't be used.

"The other limitation is that they infiltrate the surrounding brain," says Dr. Sonabend, a member of Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University. "When you think of an iceberg, you think of the part above water. Similarly, the core is easy to see, but by nature of this diagnosis, there are infiltrating cells intermingled with the brain. Or, in the case of an iceberg, they're underwater."

During an operation, the tumor core may be removed, but other cells may have infiltrated the brain. This makes recurrence likely. As a result, continued research is crucial to identify more treatment options.

Opening the Blood-Brain Barrier

One challenge in treating this complex disease is getting medications past the blood-brain barrier, a microscopic structure that protects the brain from toxins in the blood. This is like a coat of cells surrounding the brain, only allowing oxygen and nutrients to go through. According to Dr. Sonabend, the blood-brain barrier prevents the vast majority of chemotherapy medications, including paclitaxel — one of the most potent medications — from entering the brain.

Along with Roger Stupp, MD, neuro-oncologist and co-director of Lou and Jean Malnati Brain Tumor Institute of Lurie Cancer Center at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Dr. Sonabend is the principal investigator of an upcoming clinical trial to address this difficulty. Scientists created a new formulation of paclitaxel that Dr. Sonabend's lab discovered that is not harmful to the brain. "This drug is many orders of magnitude more potent than the chemotherapy currently used for these brain tumors, and the preclinical research in my lab showed it could be advantageous. In the formulation bound to albumin, it appears to be quite safe," says Dr. Sonabend. "Based on these findings, the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Federal Drug Administration have granted us the support and permission to proceed with testing to determine if this treatment improves the outcomes of our patients."

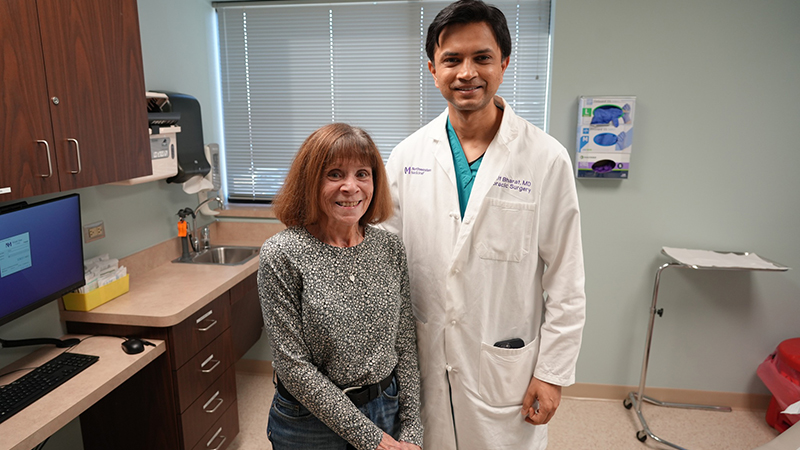

To pass through the blood-brain barrier, the medication is delivered using novel ultrasound technology placed during surgery into a window in the skull. Then, microscopic gas bubbles are injected into the bloodstream as the ultrasound begins. The sound waves cause these bubbles to vibrate, which weakens the blood-brain barrier to allow medication to pass through. Dr. Sonabend and Dr. Stupp have pioneered the use of this technology in the U.S.; as part of another recent trial at Lurie Cancer Center, Dr. Sonabend has implanted the devices and Dr. Stupp has overseen subsequent successful blood-brain barrier opening for chemotherapy delivery in several patients.

"This ultrasound technology now will enable us to use many agents established in other cancers for patients with brain tumors," says Dr. Stupp, who is associate director of Strategic Initiatives at Lurie Cancer Center and has been researching and developing new ways to treat brain cancer for more than 30 years. He is responsible for creating the "Stupp Protocol," which has become the standard of care for the treatment of glioblastoma around the world.

While other clinical trials are testing ultrasound-based opening of the blood-brain barrier, none are using an implantable version or a medication as potent as paclitaxel.

The Road Unmarked by the Pandemic

This feat has been made possible by experts coming together from varying specialties, a hallmark of Malnati Brain Tumor Institute. "It's not just one surgery or one type of treatment," explains Dr. Stupp. "They act as multiple instruments, coming together like an orchestra, with a director to make the sound to work together."

And while the world paused as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the U.S., that orchestra never skipped a beat.

"I'm grateful that we were able to offer this to patients and advance research while COVID-19 was happening," says Dr. Sonabend. "At the end of the day, individuals undergoing cancer treatment also deserve to be prioritized. The progress for breakthroughs for treatment to live longer has been slow worldwide."

During the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, several patients underwent the procedure to implant the ultrasound device and subsequent blood-brain barrier opening as outpatients.

This research applies to treatments beyond glioblastoma; the ultrasound technology may also hold promise in treatment of other conditions in the central nervous system. It could open the door for new advances in neuropharmacology, or the study of medications and their effects on the brain.

"What we are after is a new way of thinking of how to best get good drugs into the brain to help patients," says Dr. Sonabend.

Discover other clinical trials for treatment of glioblastoma.