Can You Get Eye Cancer?

Facing Ocular Melanoma: A Patient’s Journey

Updated October 2025

When Debbie Hensley went in for her annual eye exam, her optometrist knew there was a problem with her left eye.

The 66-year-old retired schoolteacher from Kingston, Tennessee, thought she might have a cataract. She was referred to a retina specialist in Knoxville, Tennessee, who diagnosed her with a detached retina. However, this was not the only concerning thing he found.

I had never even heard of eye cancer.— Debbie Hensley, Northwestern Medicine Patient

“I asked, ‘What is it?’” and he said, “‘You have cancer. You have melanoma of the eye that caused the retinal detachment,’” says Debbie. “I had never even heard of eye cancer.”

After getting over the shock of this news, Debbie collected herself and asked more questions.

What Is Ocular Melanoma?

Similar to skin melanoma, ocular or eye melanoma develops in cells that create the pigment that gives your skin and eyes color.

Ocular melanoma is uncommon, and there are two main types:

- Uveal melanoma develops in the uvea, which is the middle layer of the eyeball.

- Conjunctival melanoma develops in the conjunctiva, which is a thin clear covering over your eyeball.

Debbie’s cancer was uveal melanoma. It’s rare with only about 1,700 cases per year in the United States. It started with a freckle in the back of her eye. Over time, errors developed in the DNA of the freckle’s cells, resulting in a mutation that caused the melanoma.

Eye freckles are common and usually harmless, like the freckles on your skin. According to Chris Bowen, MD, the director of Ocular Oncology at Northwestern Medicine, only about one in 8,000 freckles in the eye will turn into melanoma.

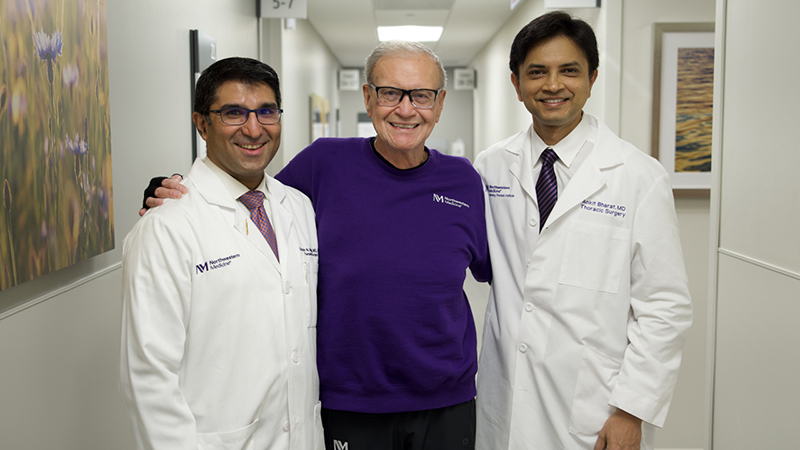

Debbie was referred to an ocular oncologist in Chattanooga, Tennessee, who recommended proton therapy since her tumor was partially wrapped around the optic nerve and was irregularly shaped. However, only a few proton centers across the United States offer proton therapy for ocular melanoma. Debbie traveled to Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, where she met Dr. Bowen and then to the Northwestern Medicine Proton Center in Warrenville, Illinois.

What Is Proton Therapy?

Proton beam therapy is particularly good at treating tumors like Debbie’s because it delivers the radiation to the exact size, shape and depth of the ocular tumor. This level of precision reduces the amount of damage to the surrounding healthy tissue, like the optic nerve and macula which are important for vision.

“Another option for treating these tumors is removal of the eye,” Dr. Bowen says. “But we didn’t want to remove the eye because we knew we could both treat this tumor effectively while keeping some vision.”

Prior to Debbie starting proton therapy, Dr. Bowen needed to perform a surgery on her eye. In a single procedure, Dr. Bowen took a biopsy of the tumor and placed tantalum ring markers on her eye.

“In order for proton therapy to be as precise as possible, we place tantalum rings on the back surface of the eye,” Dr. Bowen says. “It’s a very small, minimally invasive surgery where we place these markers in strategic locations. Then, when doing the proton therapy, the position of the rings and MRI imaging helps us determine the exact location of the tumor so the proton beam can zone in right where it needs to go.”

What’s Next?

Following that procedure, Dr. Bowen performed genetic testing and next-generation sequencing on biopsied tissue to find which mutation caused the melanoma. He used the results to create a personalized management plan for ongoing monitoring of her case.

“Fortunately, she had a favorable prognosis with both tests,” says Dr. Bowen. “We do genetic testing and next-generation sequencing because, as with all ocular melanoma cases, if the cancer spreads to other parts of the body, that’s when it starts to become especially concerning.”

Since ocular melanoma tends to spread to the liver first, Debbie’s care team will closely monitor her liver. Most of her monitoring can be done in her hometown in Tennessee with some follow-up visits to Northwestern Medicine.

Debbie has now completed proton therapy, and her prognosis is good. As the tumor continues to shrink, the retinal detachment will resolve on its own. For now, no additional treatment for her eye is needed, but she will need ongoing surveillance.

“It was kind of scary, but I trusted the doctors, and I trusted in God,” says Debbie. “I could not have asked for better. I decided I have way too many reasons to live. I have nine grandkids that I want to see grow older. You live through it, and you do what you have to do.”